Tobago is known for its abundant marine biodiversity. Trinidad is known for its one hundred-plus years-old history in the oil industry. Together, the two islands that make up this country should be both uniquely positioned to deal with the crisis of an oil spill, and motivated to protect the diverse life that calls its shores home. And yet, on February 7, 2024, a mysterious barge being pulled by a tugboat overturned, leaking a growing black stain of fuel oil into the Caribbean Sea near the southernmost tip of Tobago.

A crucial issue with a spill of this nature is how it will affect the life around it— from microscopic marine creatures all the way up the food chain to the people living in this region. I spoke to The UWI’s Prof Judith Gobin, Head of the Department of Life Sciences and Professor of Marine Biology, and Dr La Daana Kanhai, who has a PhD in Marine Ecosystems Health and Conservation, about the impact this type of spill can have on the environment.

“We need to think about the impact of the oil spill on the biophysical environment— the flora and fauna— and we also need to think about the impact on the human environment— on people,” says Dr Kanhai.

Early reports of samples taken from near Tobago revealed that the spillage was “bunker fuel”, which is considered a hazardous substance. For a spill like this, says Dr Kanhai, there are four categories of impacts to be considered for the biophysical environment: physical, biological, chemical, and ecological.

“Initially, when you have an oil spill, what people would be seeing are the physical effects,” she explains.

The dark slick covering the surface of the water, smothering sandy/rocky shores and the roots of mangroves are the first obvious signs. This can be problematic itself, because oil on the surface of the water column can disrupt sunlight entering the water and subsequently the process of photosynthesis. Oil on the roots of mangroves can compromise oxygen availability for these plants. Oil on sandy/rocky shores can smother associated fauna and disrupt important activities (foraging for food, nesting, etc).

Below the surface of the slick, it can be even more difficult to ascertain the damage, and this is an area of serious concern.

“We have not had any surveys of what’s happened underwater,” says Prof Gobin.

The Caribbean is one of the largest oil producing areas of the world, and where there is oil industry, there are spills. Trinidad and Tobago has faced several instances of spillage in the past, including the deadly 1979 oil spill in Tobago, still ranked one of the largest in the world, and the 2013 series of Petrotrin oil spills— the same year that the Ministry of Energy and Energy Affairs produced the National Oil Spill Contingency Plan. This plan is still in place, and was said to have come into effect for the most recent spill, although the Director of the Tobago Emergency Management Agency (TEMA), Allan Stewart, said that logistical support was slow to arrive.

As the days went on and the spillage continued, fingers were pointed over who was to blame. The mystery of who this barge belonged to and why it was so close to the country’s marine space without the necessary documentation, unfolded just as slowly (It was found to be called the Gulfstream, and en route from Panama to Guyana). It would be a full month before it was reported that the leaking had finally stopped. By then, the slick had spread not only to the lower shores of Tobago’s coastline, but also to neighbouring islands throughout the Southern Caribbean, extending as far as Bonaire.

“When we speak about oil pollution in the marine environment, we are speaking of a trans-boundary pollution problem,” says Dr Kanhai.

This is because oceanic currents are capable of transporting spilt oil beyond national borders. It affects life in and around the water— all manner of creatures from the microscopic plankton to megafauna like the turtles that nest on our beaches— and also affects human life in a myriad of ways. Particles of the spill, as time goes on, begin to partially degrade, and the bits that cannot degrade enter into the marine food cycle.

“The undissolved matter ends up sitting in the sediment, then fish and small organisms feed on organic matter which contain a mix of these oily particulates” says Prof Gobin. “And then they are eaten by larger organisms and this continues up the food chain. At the top, humans will then eat fish that may be contaminated, because these hydrocarbon particulates are now stored in muscle and other tissues.”

The fishing industry is not the only one that has already been and will continue to be affected by this spill. Tobago’s tourism industry will also face the consequences, as the areas in the immediate vicinity include coral reefs, beaches, and a popular bird-watching location amidst the mangrove swamp.

“You have to think of society and the economy as well,” says Dr Kanhai.

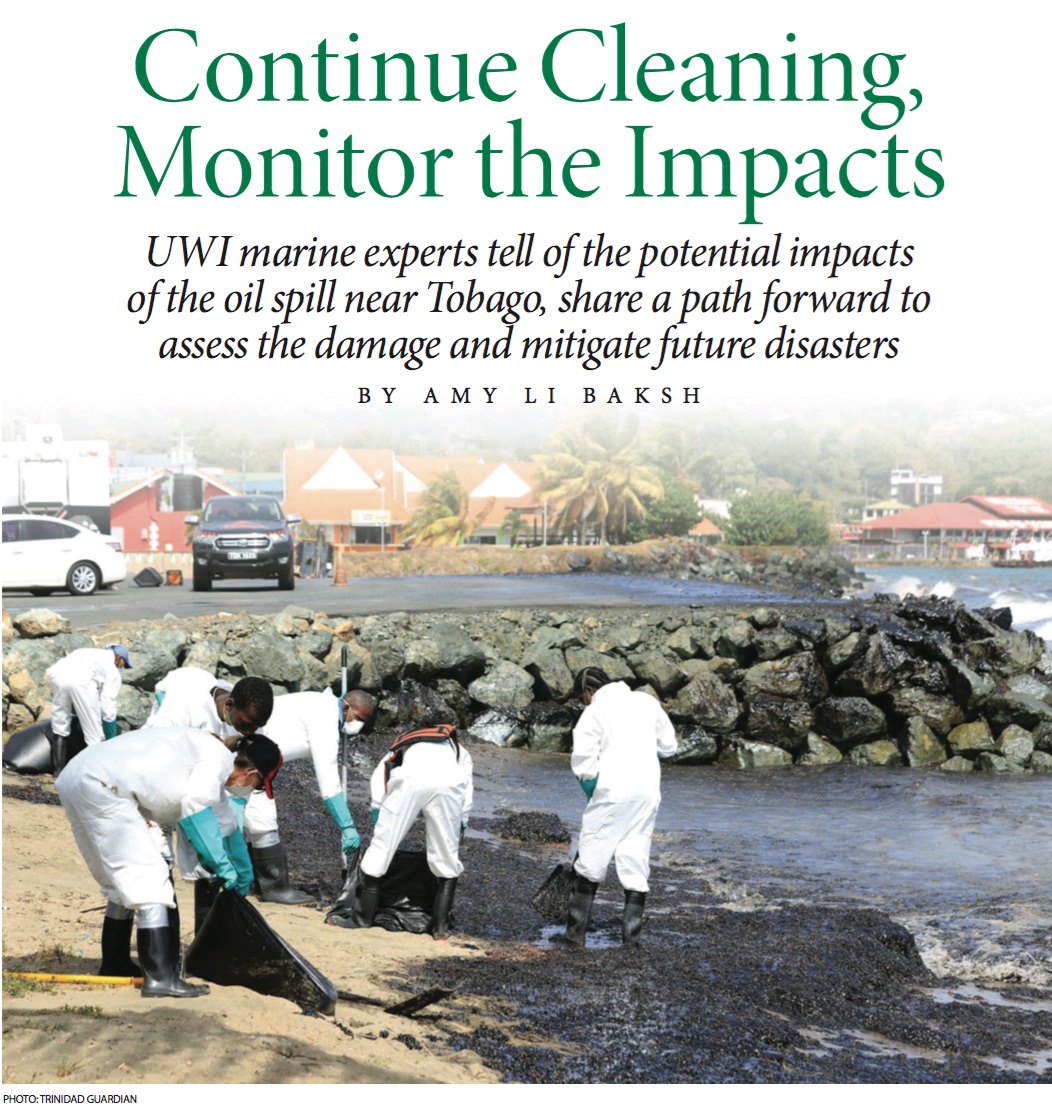

Much of the damage has already been done, and what’s left is to continue cleaning efforts and monitor to see how it will affect the surrounding ecosystems in the long term.

“It’s really a wait and see” says Prof Gobin. “This reef area has been previously surveyed by the Institute of Marine Affairs. We should have baseline data of what lived there, and in terms of monitoring, to do a survey that copies what we already know, then another in six months, and then a year and so on, to see how it changes. What we are looking for is to see what the impacts are and how severe.”

For future oil spill disasters, the hope is that the relevant bodies will be able to put into action the National Oil Spill Contingency Plan.

“It is an emergency,” says Prof Gobin. “The contingency plan clearly details what to do in these emergencies.”

Marine and human lives depend on our ability to respond to these types of crises, and when we fail, the ripple effects can be catastrophic.