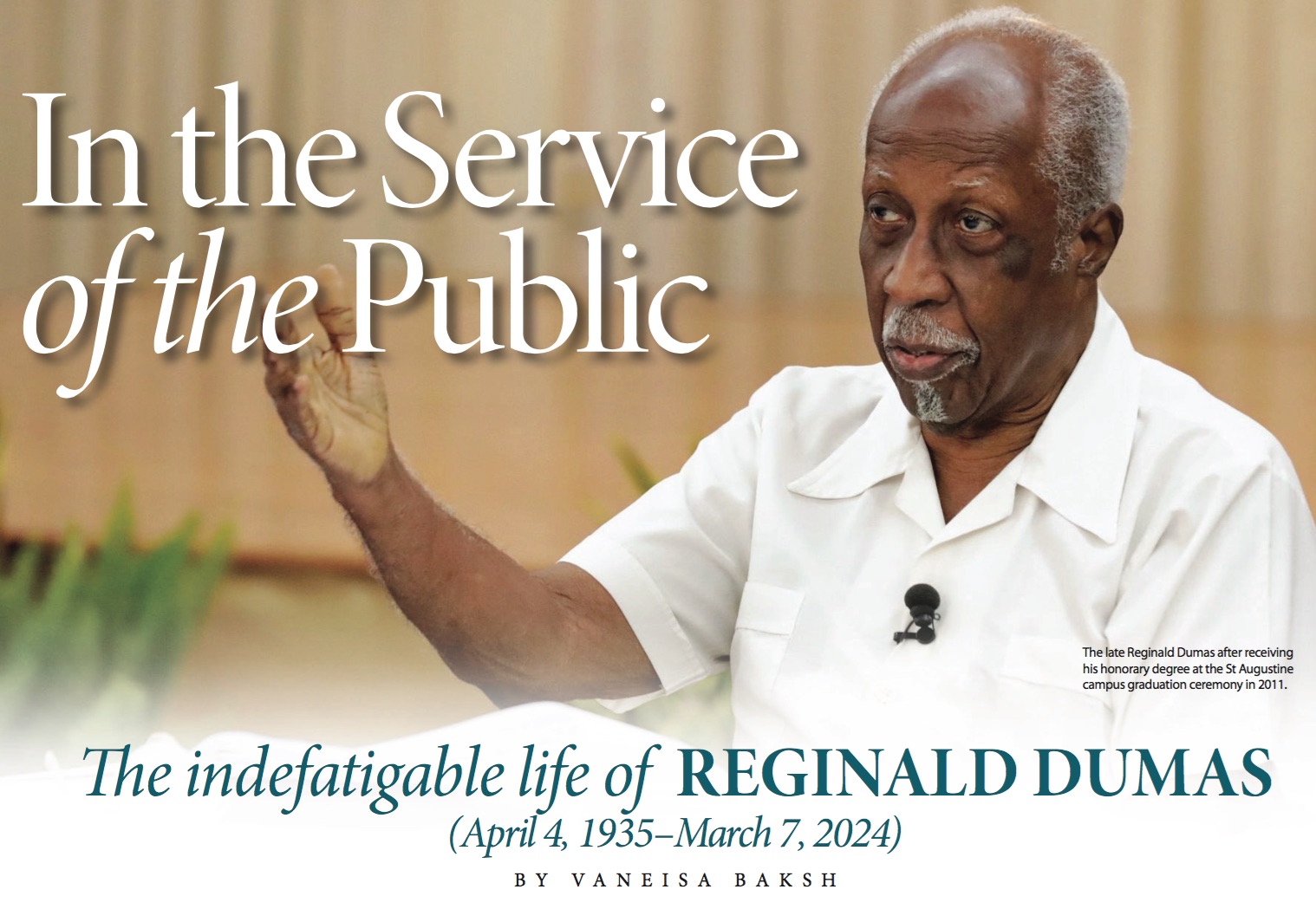

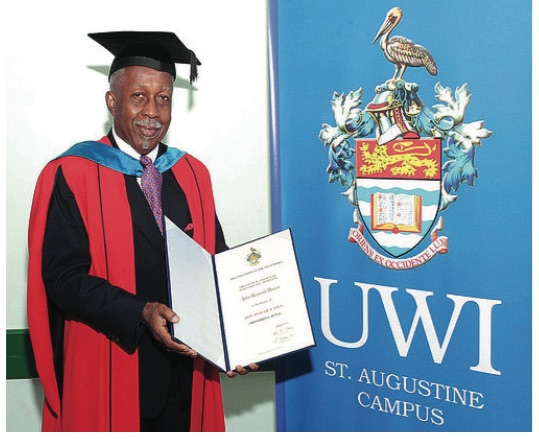

A sage, is how the public orator, Professor Paul Teelucksingh, described Reginald Dumas as he presented the citation when he was conferred with the Doctor of Laws, honoris causa in 2011.

“He is evergreen with a keen sense of transition from one age to another.”

That was certainly true of John Reginald Phelps Dumas, who passed away on March 7, just a month before he would have turned 89. Reggie, as he was commonly known, had seen radical changes in the world he’d served as diplomat and statesman, public servant and champion of regional causes, and activist of international stature. Even as he demonstrated the sagacity to adapt to the times, he never departed from the core values that held him together through many buffeting moments.

As he addressed the gathering at the graduation ceremony at the St Augustine campus of The UWI that day, he shared three bits of advice. They reflect best the philosophical outlook that elevated him to the role of human extraordinaire so that The UWI was moved to confer its highest honour on him, although he was a Cambridge man.

“It strikes me constantly that we have grown technologically at the expense of the values crucial for a civilised society—values such as integrity, hard work, community spirit, ethical behaviour, concern for the national over the sectional interest, and so on,” he said. “All these and other values influence the quality of our lives.”

He was quick to add that a good quality of life was not to be equated with ownership of expensive material goods. “Is such ownership necessary for a decent life?” he asked, reminding that “the strength of the values and of the institutional pillars of the society you live in is what above all affects your quality of life, a central element of which is your mental and psychological comfort.”

His second bit of advice was to remember that “education is not limited to the possession of a degree”. As he urged members of the audience to continuously broaden their intellectual horizons, he cited an article making a distinction between information and ideas. The author had written that humans now had more information than they could ever process, and that in the future, “there won’t be anything we won’t know. But there will be no one thinking about it”.

Finally, he said, “I implore you to keep this region constantly in the foreground of your thoughts. It is our region; it is the only one we can genuinely call ours. We must therefore do what we can to enhance its indigenous resources, intellectual, economic and other, and to strengthen its institutions—The University of the West Indies, naturally, but also CARICOM, the OECS, the CCJ, the cricket team, and so on. Nobody is going to do it for us.

“Strengthening institutions walks hand-in-hand with strengthening values. It is a long, slow, hard process. Forget about overnight success. But in that process we all benefit personally, and so do our individual countries and the region as a whole. Many persons have fought hard for this region of ours. Many have passed, or are passing, from the scene. If I have one appeal to make to you today, it is that, however difficult it may often be, and whatever your private issues, you continue that struggle, for your own sake and quality of life, and for the sake and quality of life of those around you, and those who will come after you.”

No one could have more eloquently and precisely illuminated the essence of the man than the man himself, and that is why I chose to reproduce his words here. Reggie lived by those words and his actions supported them throughout his life.

His diplomatic career, from 1973 to 1988, saw him occupying the position of High Commissioner to Barbados and the Eastern Caribbean, India and Sri Lanka, Ethiopia and other Eastern African countries, and he served as Ambassador to the United States and was the Permanent Representative to the Organisation of American States.

He wrote about those experiences in The First Thirty Years: A Retrospection (2015), Eleven Testing Years: Dissonance and Discipline (2017), and the yet unpublished manuscript of his posting in India, which I had the privilege of editing with him. Along with his other publications: In The Service of the Public: Articles and Speeches 1963–1993, with commentaries (1995), and An Encounter with Haiti: Notes of a Special Adviser (2008), (he had been so appointed by the UN Secretary-General, Kofi Anan), they make an excellent case for such narrative histories to be part of the syllabus at our educational institutions—and not just confined to history classes, but as insights into our identity as a civilisation.

Following the diplomatic career—he was one of the first group of diplomats in the Trinidad and Tobago Foreign Service at Independence in 1962—he entered another realm, serving from 1988 as Permanent Secretary to the Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago, and Head of the Public Service.

In 1998, he co-founded Trinidad and Tobago Transparency Institute, the national chapter of Transparency International. He remained committed to sharing his experience and ideas until he died, writing a weekly column in the Newsday newspaper, and frequently being sought for his opinion on various matters.

It was a life deeply embedded in the ideals he held dear, a life worthy of emulation.